I’ve often written about the nobility of nurses. My view has not changed. As far as I’m concerned, they should all be canonized. But as much as I adore them, they are often baffled by my sense of humor. Although the exchanges invariably tickle me—yes, I laugh at my jokes—they can be left in the dark.

At my fourth chemotherapy infusion, I was greeted by two twenty-something nurses.

“Hi,” the first nurse said, “my name is Raquel.”

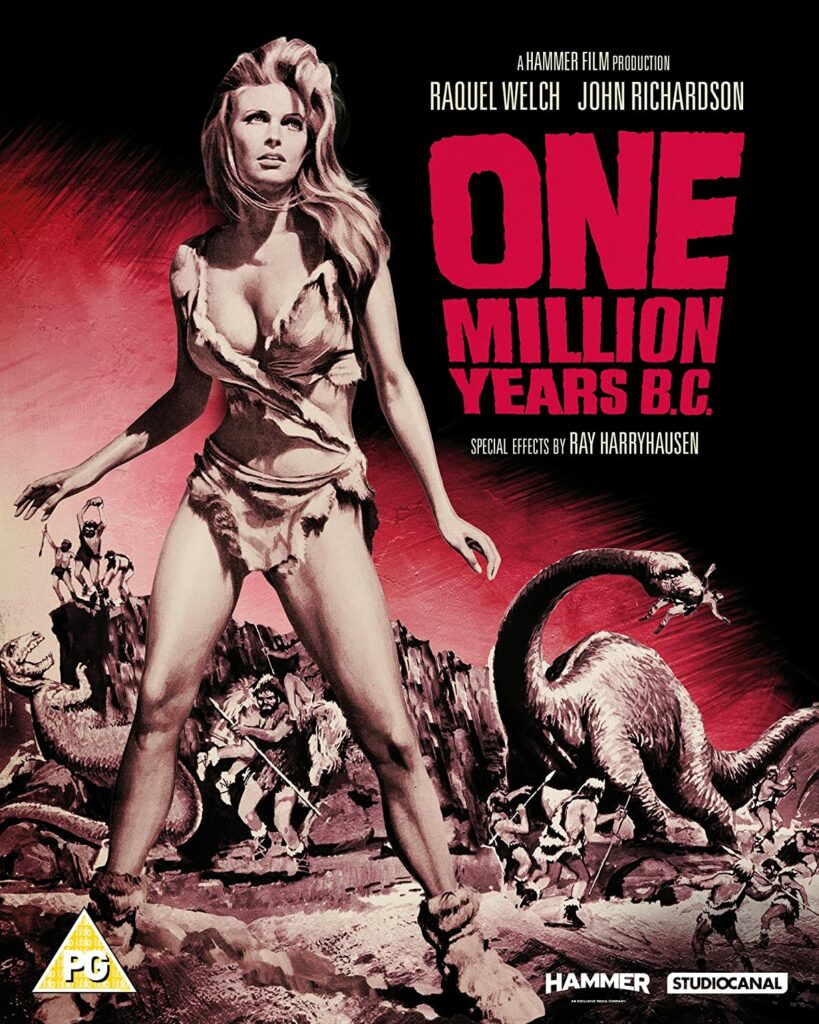

“Oh, Raquel,” I said. “What an honor to meet you. I have to say, I loved you in One Million Years B.C. You were terrific. And your costume was divine. It whispered I am summer; I am sunshine; I am the world’s first fur bikini. I loved the retro soft leather, and the hush puppy shoes were to die for.”

Raquel stared at me as if I’d just sprouted Hobbit ears.

“You know, the suede miniskirt,” I said, my voice trailing off.

“Whatever,” Raquel said.

I have to say “whatever” is not my favorite word. It’s a term drenched in annoyance, sarcasm, and snootiness. So rather than push the exchange, I did the math. I saw Raquel Welch in One Million Years B.C. in 1966 when I was a sophomore in college, easily thirty years before Nurse Raquel was born. Okay, I got it.

It was then that the second nurse introduced herself.

“My name’s Rachelle,” she said in typical perky-nurse fashion.

Without losing a beat, I sang to her, convinced she would be charmed by my crooning. “Rachelle, ma belle, sont les mots qui vont tres bien ensemble, tres bien ensemble.”

Again, I got the same unnerving whatever-stare.

Okay, the leap from Michelle to Rachelle was a stretch, but surely, she should catch the rhyme and the connection to the 1965 Beatles classic.

Nope. Only a blurry-eyed stupor.

Of course, after thinking about the disconnects, why should my ingenue nurses catch the references? In fairness, I can’t name the title of a single Taylor Swift hit. In fact, I’m not sure if Taylor’s last name is Swift, Swit, Swiss. Nor am I certain if Beyoncé is a singer or a fabric softener.

A few minutes after the awkward introductions, Raquel was ready to poke a syringe into my mediport.

“This should go in smoothly,” she said. Then, in what seemed either an afterthought or revenge, she asked, “What’s your tolerance for pain?”

Going for cutesy, I said, “I’d place myself somewhere between a colic baby and a whining puppy.”

My quip did not get a giggle, which was understandable; it was not particularly laughable.

Raquel faced me, place her arms akimbo on her hips, and said, “Oh, in other words, you’re like a man.”

That made all of us howl.

“I thought my line was decent,” I said, “but you bested me by a mile. I’m going to use your line.” And so I have.

***

My infusion session was accompanied by Elaine Chapman, one our key support-team members.

Although I’ve spoken of Elaine before, I’d like to round out her character.

Elaine and I are different in many ways. She’s a scientist; I’m an artist. She’s an introvert; I’m an extrovert. She’s a wallflower; I’m a flaming peacock. And, yet, I’m hopelessly drawn to her caring spirit.

Elaine was raised in the pastoral township of Danville, Vermont, where she developed her skills in basketball, softball, and cross-country.

Although Elaine’s mother was loving, she was hampered by heart disease, a condition that shrouded family tranquility. Because Elaine’s father was ill at ease with doctors, the job of arranging medical appointments fell to Elaine. That experience was pivotal in developing Elaine’s aptitude for caring for others.

Elaine graduated from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York where she juggled co-captaining the basketball team while studying chemical and environmental engineering.

When I asked why she chose engineering, she said, “I knew the career would be rewarding enough to help my parents.”

“Was it tough being enrolled in a male-dominant university?” I asked.

Elaine pursed her lips. “There was a range of reactions. Some scoffed at female students. Most accepted our presence.” Then Elaine added a thought that marked her nobility. “As a model for all women who pursued a male-dominant career, I was driven to excel.”

I shifted topics. “Tell me who you are?” I asked.

It did not take long for her to respond. “I care deeply. I’ve learned that making life easier for others enriches my life.”

I smiled. That was a perfect summary of Elaine’s character. “Could you say a bit more?” I asked.

“When I help others,” she said, “they’re usually more content. That’s gratifying, but more importantly, I become a more decent human being.”

I went to my go-to final question. “What would you like inscribed on your tombstone?”

After reflection, Elaine said, “She cared not that she won or lost, but how she played the game.”

At the end of the day, Elaine drove me home and walked me to my front door. Before entering, I turned to her. “You’re an enigma to me,” I said. “You’re so caring and yet so hesitant to risk a hug. Why is that?”

“You have to remember I’m from Vermont,” she said, “where people are reluctant to be emotionally vulnerable.”

“Okay,” I said. “I respect that.” I reached out to lightly tap her elbow, all the while wondering if that timid expression of affection was overly daring.

Elaine turned and gave me a solid hug. If she had any misgivings, they were well hidden. It was an embrace that felt genuine—not that I was keeping score. I just enjoyed the warmth.