After Nita’s death, I often heard a rustling or an inexplicable shift in air current. Without thinking, I looked over my shoulder to catch a glimpse of her.

No, she was gone—an agonizing reality. Still, I wanted her by my side.

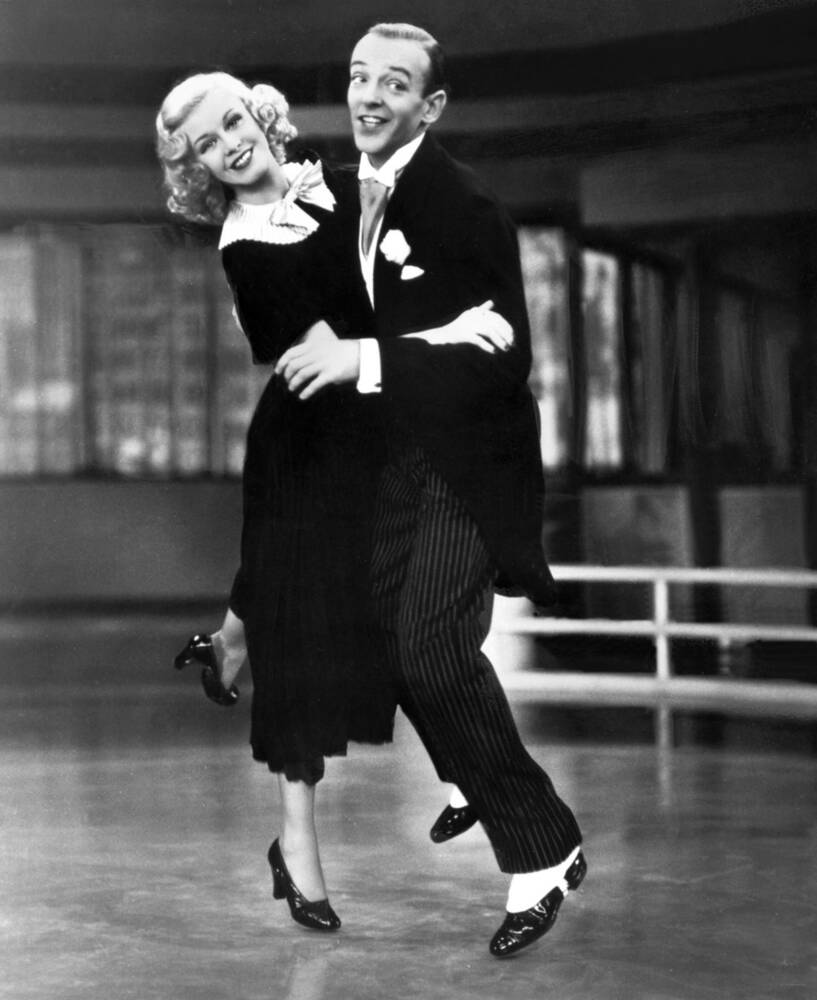

For some who have lost their spouses, the evenings are the dreaded time of the day. Not for me. Eventide was when I felt closest to Nita. I watched the old movies that she loved: Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn, William Powell and Myrna Loy, and the third season of All Creatures Great and Small.

How I loved those films. Although Nita was no longer present, I let my hand slip to her side of the bed when Astaire and Rogers kicked up their heels. Their dancing was so elegant, so perfectly synchronized, I wanted Nita to capture the moment of supreme artistry.

“Did you see that?” I asked. “The way they held each other—softly, tenderly—as if they were fragile orchids where the slightest grasp would crush the other.”

Although there was no answer, it did not stop me from feeling Nita deep in my soul, a region without locus but real nonetheless.

***

I was new to grief, but a telephone call from my cousin, Basil, helped me frame my emotion.

“I’ve been thinking about you,” Basil said. “Wondering how your days are playing out.”

“It’s strange,” I said. “When I’m alone, one day drifts into the next without incidence. But when people visit, it’s another story.”

“How’s that?” Basil asked.

“I don’t weep when I’m alone. Somehow, I’m able to take the solitude. But when I’m with a friend, and I see tears welling in his or her eyes, the emotion rolls in like a wave. And when the wave breaks on the shore, I find myself sobbing as if the world were coming to an end. It starts with my breathing—shallow heaving that breaks into tears. My throat is seized. I am a prisoner of my own grief.”

Basil was silent.

“It’s impossible to speak when that happens. If they keep their distance, I can wait for the sobbing to subside. If it is a woman, she is almost always compelled to move to my side and cover my hand or, more often, wrap her arms around me. Then the sobbing continues.”

“The human connection,” Basil said.

“Yes. When I feel their compassion, their sorrow, their love, the heaving in my chest becomes uncontrollable. All I can do is wait.”

“What then?” Basil asked.

“If I’m physically touched, it takes longer, but eventually I’m able to take a deep breath. There is no need to apologize. Those who love me don’t require contrition. They’re willing to sit in silence until I’m able to gather my thoughts. But here’s the thing, Basil. That moment of connection is always cathartic. It is as though my heart and mind were swept clean by an ocean breeze. I can breathe. And what is more, I can live again.”

***

I had one last love song to sing before moving on. I needed to host Nita’s Celebration of Life Gathering.

Although our home was spacious, we were probably a fire hazard with over fifty friends and family in attendance. Even five of my high school classmates arrived to honor Nita.

The crowd was perfectly quiet, allowing every word spoken to be heard.

The gathering would not be gloomy. That was not Nita’s style. I had Debi Eng at the piano, Phil Simpson on bass, and Frank Eng on drums. They were all accomplished musicians with whom I had jammed for decades.

The most jovial moment was when I introduced what I called “the audience participation bit”—something I included in every jam-session performance.

I brought the microphone close to my mouth. “This was always Nita’s favorite part of the show. Why? Because it dismissed me and allowed others to shine. Yes, my wife was well aware I was a showman down to the bones and, if given the opportunity, could run away with a performance. I once heard Nita say from a distance ‘Allen is not a ham. A ham can be cured.’ That’s why we’re doing the audience participation bit—in honor of Nita’s wisdom.”

I moved the microphone stand down center stage. “I’ve always been awed by the musicianship of Louie Armstrong,” I said. “His mixture of song lyrics with scat singing was always a wonderment to me. I can’t do it alone, but I can do it with a little help. Tommy Oleson, would you help me?”

Tommy jumped from his chair. I think he may have burned a patch of carpet on takeoff.

“I take it you’re ready to do this,” I said.

“Oh, yeah,” Tommy said, his eyes rounded.

“All right. Let’s cook.” I paused long enough to start my internal metronome. “You are my sunshine, my only sunshine.”

What I expected from Tommy was something like, “Wee-be-doodle-ee, bee-doodle-dee-chow.”

I held the microphone to Tommy’s mouth, and he scatted, “Ooh.”

I cocked my head. “Sparse but nice.”

That was it—a single note—but sufficient to garner a warm laugh from the audience. That’s the great thing about audience participation. Whatever is offered works.

But there was something else going on. When Tommy was five, he and his family became our next-door neighbors. I have watched Tommy grow into a dazzling young man—one who is a deep thinker, a versatile artist, and a spiritual pilgrim. I have met many young people in my lifetime, and I love them all. But I love Tommy a little more. Perhaps the audience detected our mutual devotion.

So many kind words were spoken in celebration of Nita. She was characterized as one who had the patience of Job, the tenderness of Mother Teresa, and the elegance of Audrey Hepburn.

At the end of Nita’s tribute, it was my turn to speak. I expelled a deep sigh. “The last three weeks, Nita was incomprehensible. But before that, I sat on the side of her bed, and I took Nita’s hand”—I turned my head to the side to halt my weeping—“she said the most beautiful three words. ‘I love you.’”

“Nita was so truthful, so honest, so much like a butterfly that flittered from flower to flower, spreading their seeds of beauty. In a word, she was always loving—putting the cares of others before her own disquiet.”

I took another withering breath. “I’ll be honest with you,” I said. “When I found myself in a hard spot, I often composed a letter. Before sending the missive, I would read it to Nita. And she would say something like, ‘Well, that’s very articulate, honey. But you might want to soften the part about suggesting they jump off a cliff.’ Whatever counsel she had for me, it was always wise and gentle and composed. By her example, she taught me how to care for people. Her last words were, ‘Love others, even when they seem unlovable.’ That will always be my remembrance of Nita. When it comes to spirituality, she was my mentor.” After Nita’s celebration, I lost track of time. I slept for ten, even twelve hours a night. But I was not tormented. It was as though all the love expressed for Nita also weaved a cocoon of intimacy around me. I felt exquisitely serene. Yes, I deeply missed her. But she spent a lifetime preparing me for her absence by being selfless and intent on helping others to be the most mature, most loving versions of themselves. That’s how I would survive: by following her lead—by dedicating whatever days remained to what I call “servant leadership.”