Unless you or a loved one has been diagnosed with bladder cancer, you might choose to skip this chapter. It’s a bit technical. At least as technical as I, a layman, can describe it.

I’ll be explaining two procedures: the placement and removal of a ureteral stent and an immunotherapy called BCG. Don’t worry. I’ll clarify the terms as I go.

***

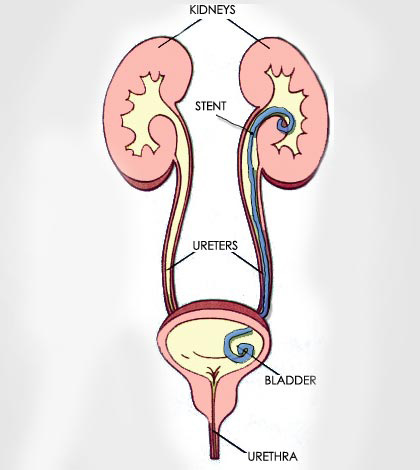

The ureters are the ducts that transport urine from the kidneys to the bladder. My surgeon explained the complication. One of the ureters was close to the tumors that needed to be scraped out of my bladder. (By the way, the medical term for scraping out tumors is called “transurethral resection of bladder tumors.” Now you know why I say “scraping.”)

To deal with the problem, my surgeon moved the ureter to safely resect the tumors without damaging the ureter. After scraping out the carcinomas, the ureter was reimplanted into the dome of the bladder close to its previous location. Then, a hollow tube called a ureteral stent was placed inside the duct to keep it from collapsing.

The stent stayed in my body for six weeks. During that time, my urine was red with blood and often blackened with clusters of blood clots.

When the stent was removed—a glorious day—it was a surprisingly quick and painless procedure. The critical tool was a cystoscope, a thin tube-like instrument with a light and lens for viewing. My local urologist, Julio Slongo, expertly inserted the cystoscope through the urethra and into my bladder. Using tiny clamps attached to the cystoscope, he pinched the stent and gently drew it out of the ureter, into the bladder, through the urethra, to Grandmother’s house we go. The stent was extracted in a single motion as gently as drawing a thread through a button hole. The sensation was so liberating I was tempted to kiss Julio on the lips—an urge I resisted. We’re close but not that close.

This is the best part. Immediatelyafter the removal of the stent, my urine was crystal clear. I mean pristine. Rocky Mountain spring water is more murky.

All the blood and blood clots were due to the irritation the ureter sustained by the stent.

There was another benefit. As long as the stent was in place, I felt a twinge each time I stood or sat—the splint reminding me it did not bend and twist the way I did.

When the stent was removed, I felt I made a thirty-percent advancement in my recovery.

***

Surgery is only the first leg of managing bladder cancer. Immunotherapy is the next step—a long and winding road. The go-to immunotherapy is called Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, what everyone calls BCG for obvious reasons.

BCG was developed by two French immunologists in the 1920s. Interestingly, it’s made from a weakened strain of their vaccine originally developed to treat tuberculosis. Today, the infusion of BCG into a compromised bladder prompts the immune system to attack the cancer cells.

The therapy was particularly important for me. Although my bladder cancer was not muscle invasive (a good thing), the cancer was aggressively high grade (a bad thing). That meant the cancer was likely to return, which is why BCG was so important. If I refused the treatment—my right—there was a seventy-percent chance the cancer would return. After undergoing the induction treatments, the chance of the cancer rebounding dropped to forty percent—not perfect but better. If I follow-up with a series of maintenance treatments, the cancer is only twenty percent likely to return.

The induction series of BCG treatments occurs once a week for six consecutive weeks. It’s followed by three maintenance treatments that are conducted six to eight weeks after the final induction treatment. Depending on the BCG results (and the will of the patient), the treatments could continue for two to four years.

My first BCG treatment was scheduled for two months after my surgery. It was not pleasant. A nurse—invariable the age of my granddaughter, if I had a granddaughter—began by injecting a five milliliter dose of lidocaine into my urethra.

When she extracted the syringe, she said, “Squeeze the tip of your penis to keep the lidocaine in.”

Okay. That works for me.

That was the fun part. The pain followed with a vengeance when the same perky nurse threaded a catheter into my penis. When she passed the prostrate, I groaned. When she nipped at the sphincter, I yelped.

“Try to relax,” she said.

In my life, I’ve heard people say lots of stupid things. A housewife once told me she never worried about paying bills as long as she never opened a statement. Another said he was sure France bordered England. A third confessed, “I don’t know if an egg is a fruit or a vegetable.” But the kicker was when the nurse demanded I relax when she jammed a rod into my sphincter whose sole job is to squeeze shut when pushed.

“I’m trying, I’m trying,” I squawked.

When she shoved for home, and I whooped again, she said, “I’m coming out.”

“What d’ya mean you’re coming out? You can’t leave me unfinished.”

The nurse slipped the catheter out in a flash. “I just had a thought,” she said. She turned to the medical tray and stared at the catheter’s packaging. “This is a French-16 catheter,” she said.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“It means the diameter is 5.33 millimeters—a number calculated by dividing sixteen by three.”

I squinted to hear better. “What are you saying?”

“I’m saying we should try a French-14.”

I immediately thought of a French friend who hunted sangliers(wild boars) in Aveyron with a twelve-gauge shotgun which was definitely bigger than his sixteen-gauge shooter. If the French calibrated catheters the same way they calibrated shotguns, a French-14 would be BIGGER than a French-16.

“Wait a minute,” I said warily. “What’s the diameter of a French-14?”

“It’s smaller,” the pubescent nurse said. “Only 4.7 millimeters.”

I turned my palms open and bobbled my head sideways like a hip-hop dancer. “Yeees!” I said, my voice a clarion wail. “Get it!”

When the nurse left the room, I practiced my deep-breathing exercises.

She returned in less than a minute with a French-14 and inserted the catheter with relative ease—not harmlessly, but within reason. She then pumped ten milliliters of sterile water into the catheter, which ballooned the tip of the tube, preventing it from slipping out before the job was done.

The rest of the procedure was a snap. Julio stepped into the examination room, injected fifty milliliters of BCG into my bladder, deflated the catheter balloon, and slipped the rigging out.

After the procedure, I told Julio I was glad the nurse had thought of going with the smaller catheter. “It really helped,” I said. “I suspect some men are braver than I, but even they are more cowardly than any woman.” Then—even though we were alone—I added in a muffled voice, “This misery would not be so bad if I were a porn star. But I’m not hung like a horse. I’m hung…like a hobbit.”

Julio quickly stifled a chuckle. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I shouldn’t laugh”—as if his tittering could somehow damage my sense of machismo in this, the three-dog winter of my life.

When the nurse returned with the discharge papers, she reminded me to hold the BCG cocktail in my bladder for two hours (which I had no trouble doing). She also warned that I might experience fatigue or flu-like symptoms, neither of which happened.

***

I was steely-eyed and gung ho to send my immune system to war. As I drove home, I imagined elfin soldiers slugging cancer cells below the belt where it hurts—just to get even.

That afternoon, through the evening, and into the next morning, the tip of my penis trickled with blood. If my legionaries were victorious, it was not without casualties.

A week later, for the second BCG infusion, I asked the doctor why I bled when the catheter was removed.

“The catheter is a foreign raider—not something the body tolerates,” he said. “In brief, the bladder was pissed,” which pretty much described my sentiments.