Shelly worked at the Cancer Center. I didn’t know her last name. I only placed her by her smile, which was radiant. Why she took to me was a mystery. Perhaps she felt a connection by reading chapters from In Defiance of the Night. Maybe she was reminded of her husband who she lost two years earlier. Whatever the reason, she greeted me with an embrace devoid of reticence or timidity.

Not everyone knows how to caress another. Some favor a side hug, which is like given a hamburger without the meat or cheese. Others construct an A-frame edifice as if approaching anything below the belt were defiled by Satan. These were not Shelly’s methods. Her embraces were given straight up—tenderly, wholeheartedly—each hug feeling like an infusion of red blood cells and hemoglobin but without the slow drip of time. I was compelled—no, moved—to return her caress with equal fervor.

I mention Shelly as one of many who eased my journey. Shelly was the master of cuddles. Others were adept at touching me with their words of comfort or a tasty dessert or a heartfelt conversation.

That human connection never faltered throughout my medical trials.

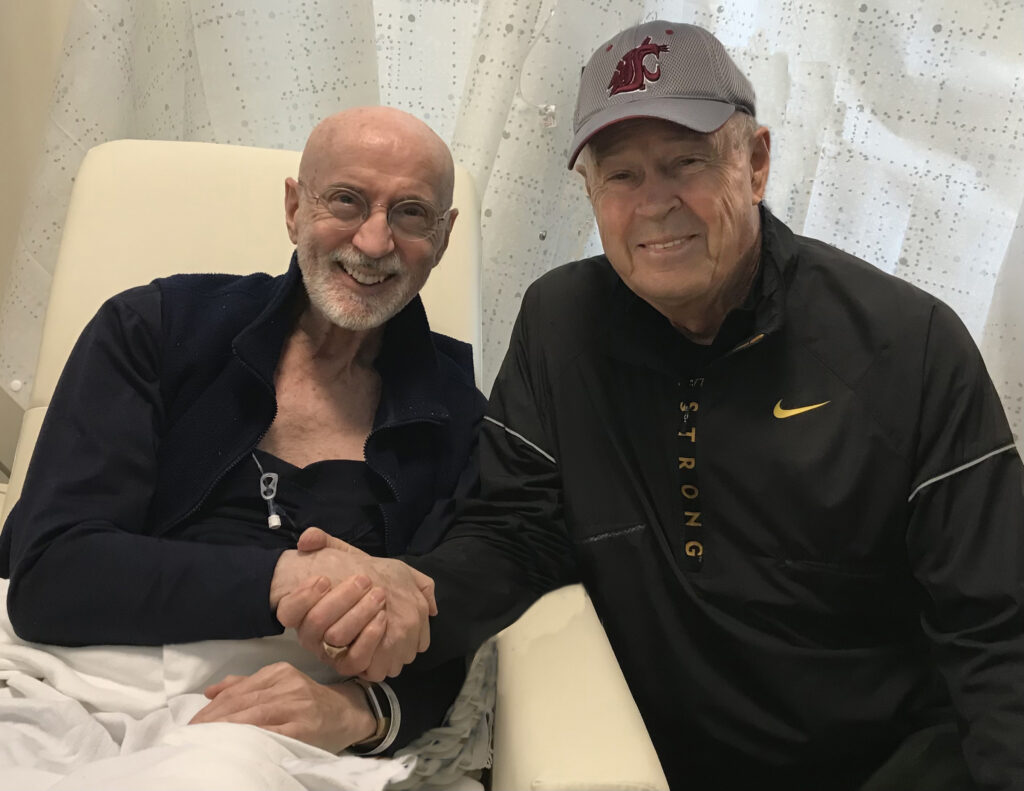

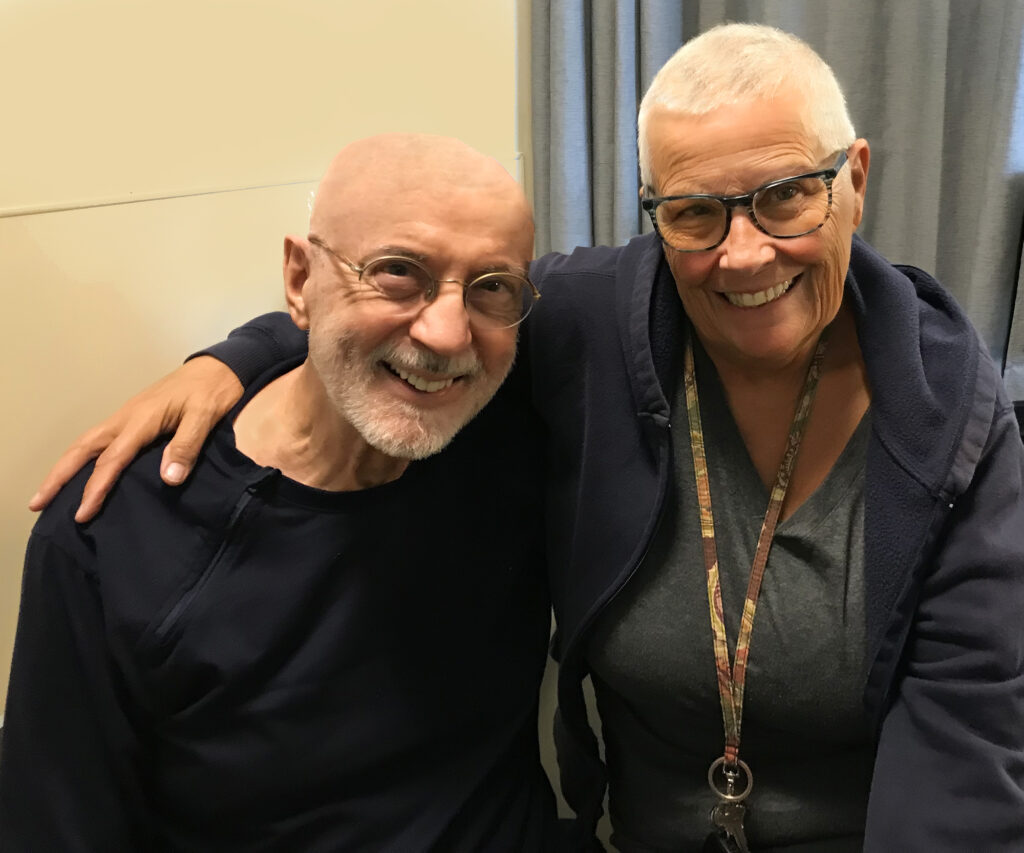

Before describing the last chemotherapy infusion, I’d like to pay tribute to three friends who gifted me with their most precious asset during my final chemotherapy treatments—their time.

***

Bill Leonard had the heart of a country boy. There was a gentle sweetness about him, perhaps cultivated by his upbringing in the pastoral farming community of Grand Forks, North Dakota. He was not particularly motivated in high school and even less so at the University of North Dakota.

“I was asked to leave the University for academic bungling,” Bill said. “In fact, I didn’t know how to spell ‘academic,’ and I wasn’t sure about the meaning of ‘bungling’ though I had a hunch it wasn’t a compliment.”

For the next two years, Bill rode the back of a fire truck pumper. “I’ve never been so cold in my entire life,” he said. “I soon realized firefighting was not my life’s goal.”

“What was?” I asked.

“When I was in high school, I worked at the YMCA,” Bill said. “I discovered I could relate to kids.”

Bill decided to enroll at what is now North Dakota University where he majored in Elementary Education and, upon graduation, landed a position as a sixth-grade teacher in Fontana, California.

“Three years later, I discovered my real calling. I moved to San Bernardino. It was there that I eventually became the principal at the Verdemont Boys’ Ranch.”

“How long were you there?” I asked.

“Nineteen years.”

“What was it like?”

“It was not easy,” Bill said. “The boys were wards of the court. For many of them, going through juvenile hall was a rite of passage. But there were success stories. Although it was difficult, families sometimes stepped up and broke the cycle. And that made all the difference.

***

Amadis Rondon is a new friend. I met her when strolling from our home to an adjacent neighborhood. Even from a distance, I could tell she was no ordinary teenager. Twenty paces away, her smile was effervescent. And when she approached, she did not quicken her pace and divert her eyes to the side of the road as many teenagers tend to do. No, not Amadis. She slowed her tempo, came to a stop, gazed into my eyes, and said, “Hi, I’m Amadis. What’s your name?”

Her warmth was so genuine and disarming, I had to chuckle out of sheer joy. “I’m Allen,” I said with a nod of respect.

“It’s nice to meet you,” she said, her tone percolating as if she had caught sight of a spring lamb cavorting in a field of green. She was not a lackluster acquaintance; she was a phenomenon.

“I’m homeschooled,” she said in rapid fire. “I like reading and writing the best. And pretty soon, I’ll graduate. And then, I’m off to college. I’m not sure what I’ll do—not yet. Maybe I’ll be a nurse. My father’s an ophthalmologist. I don’t think I want to follow his lead, but maybe I could. I don’t know. It’s possible. I’m just not sure right now.”

If her speech were not delivered in one gasp, it was separated by a single catch-breath too brief to detect.

From that first introduction, I hoped our paths would cross each time I went for a walk.

There were other meetings, and although I was invariably tickled by her exuberance, the conversation was always lopsided. The teacher in me could not resist the opportunity.

“I have a question for you,” I said.

“Oh, how wonderful,” Amadis said. “What is it? Tell me.”

“You are such a treasure,” I said. “And I think you have the personality and the intelligence to understand something I’d like to share.”

“What is it?” she asked, her pitch a tone higher.

“I’d like to teach you the art of conversation. Are you interested?”

Her energy was boundless. “Oh, yes,” she said. “That would be fabulicious.”

“Fabulicious? That’s not a word I know. Did you make it up on the spot.”

“I don’t know,” she said. “It just popped out before I could put on the brakes.”

Because I had not yet met her parents, I suggested her mother join us at my home. A few days later, we had our first session.

Amadis’s mother, Betty, was a mature version of her daughter. If I were judging their smiles, I would be hard-pressed to select one brighter and more inviting than the other.

Clearly, Betty was a woman of intellect and charm. And yet, she seemed oblivious to the depth of her wit and appeal, which is indicative of the most important quality of all: humility.

“There is something immediately engaging about you,” I said to Betty. “I’m wondering if you came into this world with a penchant for warmth and kindness or if it was something you perfected over time. Or perhaps it’s a delicious goulash of both nature and nurture.”

Betty flashed her beaming grin. “When I was a child, I wanted to collect shooting stars. I soon learned they were allusive marvels. But I could collect streams of light I encountered in my daily life. It’s easy to see you’re a spectacular shooting star.”

With a wink, I said, “And you make a tasty goulash.”

“Well, I do scramble a pretty good stew.”

“No, you misunderstand me,” I said. “You are a tasty goulash.”

Betty reached over, tapped my knee, and let go a cascade of giggles. “Oh, you’re a charmer,” she said, wagging her finger at me.

“It’s easy when it’s the truth,” I said. “I just wish my metaphor were as picturesque as your shooting star.”

With that exchange, I launched into the lesson. “Amadis, we’re going to pretend you and I are meeting for the first time.”

“Oh, like acting,” she said. “I love this.”

“You begin,” I said.

She didn’t waste any time. “Hi, I’m Amadis. Who are you?”

“I’m Allen.”

Amadis paused. She was stymied. “I don’t know what to say next.”

“Would you like to know me?” I asked.

“Yes, of course.”

“Then ask a question.”

Amadis thought a moment. “You have a lovely home. Did you build it yourself.?”

“No,” I said. “I had it built.”

Silence. Amadis was stuck again.

I glanced at Betty. Her eyes were sparkling, her smile knowing. “Amadis,” I said, “try asking an open-ended question, one that cannot be answered with yes or no.”

Amadis looked down and to the side, her chin cradled between forefinger and thumb. She smiled. “Allen, would you tell me something about yourself?”

“Wow! That’s great,” I said. “That’s as open-ended as you can get. I can go anywhere with that. I can tell you about my passion for music or writing or language. I can share my love for friends or my take on spirituality. You’ve opened a world of possibilities.”

What followed were key interpersonal communication lessons: how to listen empathically, how to keep time speaking and listening relatively equal, and how to employ follow-up questions to fully understand a person’s worldview.

That was the beginning of what has become a beautiful friendship. In fact, the Rondons—including Betty’s husband, Oswald, and Amadis’s older brother, Amedeo—have adopted me into their family. And, if that were not enough, Amadis now calls me her “Bestie Uncle Allen.” I don’t think I’ve been anyone’s ‘bestie’ before. Although new territory for me, I’m happy the kinship is with the irrepressible Amadis. I just hope I can keep up with a natural fireball.

***

I’ve known Debi Eng for well over thirty years. In the early 1990s, she was serving tables at the Country Gentleman. I knew her indirectly through her husband, Frank Eng, who graduated from Pasco High School in 1962, two years before me.

Both Debi and Frank were sensational jazz musicians—Debi on piano and vocals, Frank on drums. And although Debi would always describe waitressing as an honorable profession, there was something inside that yearned for more.

Ted Neth, who was the chairperson of the Department of Performing Arts at Columbia Basin College at the time, had a part in kindling the urge. Debi waited tables on the weekdays and gigged on the weekends. When Ted heard Debi perform, he knew she was something special.

On a break, Ted said, “Debi, you need to teach and, so doing, leave a legacy. It’s time for you to go back to school.”

Debi did the math. “By the time I earn my BA, I’ll be forty years old.”

Ted had a response in his pocket. “True. In four years, you’ll be forty. But you can be forty with a degree, or you can still be waiting tables. Where would you rather be?”

About the same time, I was also encouraging Debi to make the leap. And so she did. In 1994, she graduated from Central Washington University with a bachelor’s in music. For the next twenty years, she taught music at middle and high schools. Today, a number of her former students are either teaching music or performing. “There’s nothing better than that,” Debi said.

When I asked for Debi’s tombstone engraving, her response was predictable. “Music is the way to spread love and peace,” she said. “My engraving is ‘Music is god, god is music.’”

***

On May 4, 2023, I had my last infusion. The process was familiar. The nurses repeatedly asked for my name and date of birth. They fed me anti-nausea medicine and a half liter of Gemzar chemotherapy.

The only difference between my first and last infusion was my loss of hair. Before you ask, “What hair?” let me explain. The fleece that disappeared was not from my dome—I haven’t had a head of hair for decades. I’m talking about the tufts from all other regions: ears, armpits, legs, arms, chest, and zones whispered afar from mixed company. It all disappeared. (Well, almost all. Mercifully, although my iconic beard was thinned, it was not entirely harvested—a meager kindness.)

When I stared at myself in the mirror, I looked like the prepubescent twelve-year-old in the shower after gym class—slippery as a fish from head to toe. If I were still swimming, I was sure my time in the one-hundred-meter breaststroke would be liquified.

Although Debi Eng was with me on my last infusion, I did not speak to her about my glossy hide. If fact, it was she who opened the conversation on a more seemly topic. “I see why you like it here,” she said. “It’s true: you’re treated like royalty but for good reason.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“You’re always looking beyond yourself. Even now, while the poison is pouring in, you’re focused on my life, not your fragile condition.”

“I have lots of time to think about my misery,” I said. “I don’t want to waste a minute when I’m with you.”

“That’s what I mean,” Debi said. “You’re looking outward, not inward. And that’s why the staff loves you.”

Almost on cue, my cubicle curtain was thrown back. Twelve oncology nurses approached, presented me with a bottle of sparkling cider, and sang new lyrics to the tune of “Happy Birthday.”

“Congratulations to you.

Your chemo is through.

Enjoy and remember

We’re all here for you.”

I couldn’t stop my face from grinning like a jack-o’-lantern. “I love you all,” I shouted.

“That’s so sweet,” one of the nurses said.

When it was time to leave, I was asked to ring the bell hanging near the infusion center entrance. When I did, I was greeted with rousing cheers from all the nurses who encircled the grand room.

“Incredible,” I said to Debi. “Every nurse here is one in a million.” I shook my head and smiled. “Mathematically speaking, how is that possible?”

How indeed?