There’s a familiar American idiom: “when it rains, it pours,” meaning when bad things occur, more misfortunes are likely to follow. Perhaps the original colloquialist was a farmer thinking about floods followed by swarms of locusts. Though the scale is smaller, the saying applies to me because pestilence has traveled from my pelvic floor to my cranium.

A week before my scheduled fourth and final cycle of chemotherapy, I was annoyed by throbbing pain above and behind my left ear. The nagging was unrelenting. When I mentioned it to my oncologist, he recommended an MRI scan of my brain.

Two days later, I received a call from my oncologist.

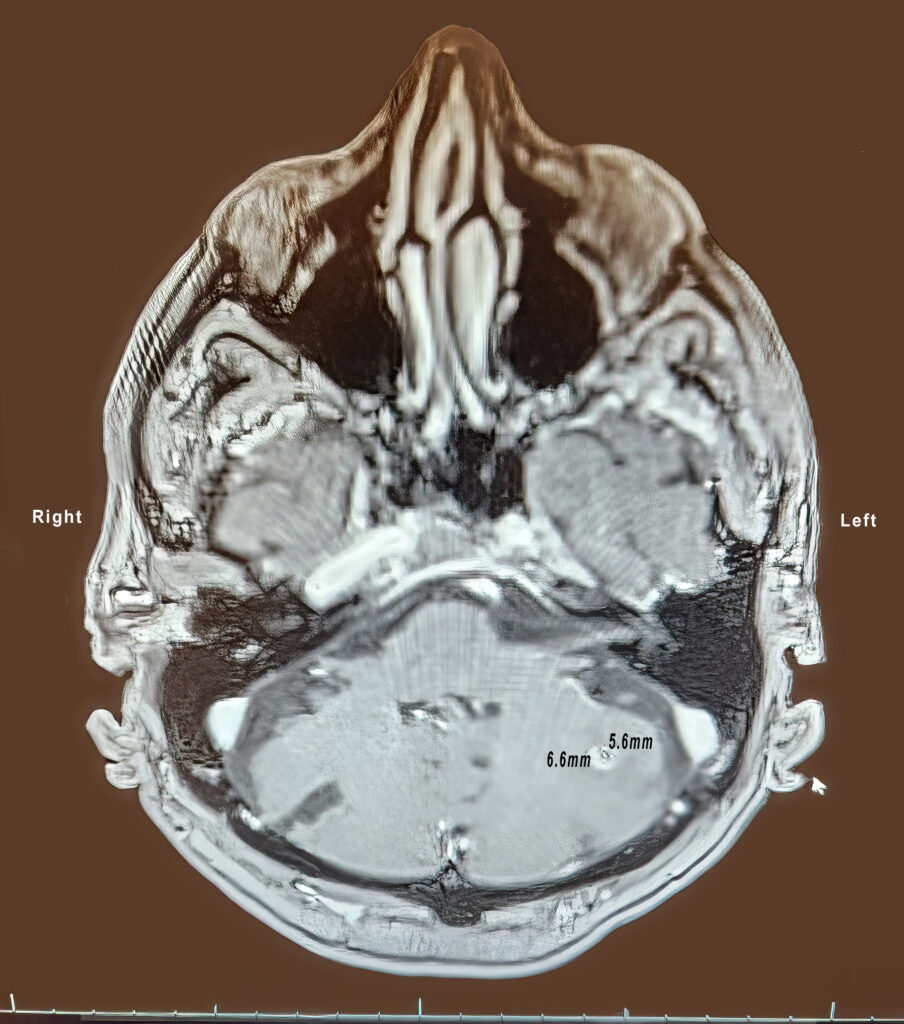

Never one to dilly-dally, the doctor said, “Allen, the scan found a lesion in the cerebellum. It’s small, approximately six millimeters, about a quarter of an inch in diameter.”

“On the left side?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“Could that be the source of my headaches?”

“It’s possible,” he said, “but I’d like you to speak with a radiation oncologist.”

***

Two days later, I was in the office of a radiation oncologist who knew me from my writings. For the telling of this story, she preferred to be called Dr. Sue.

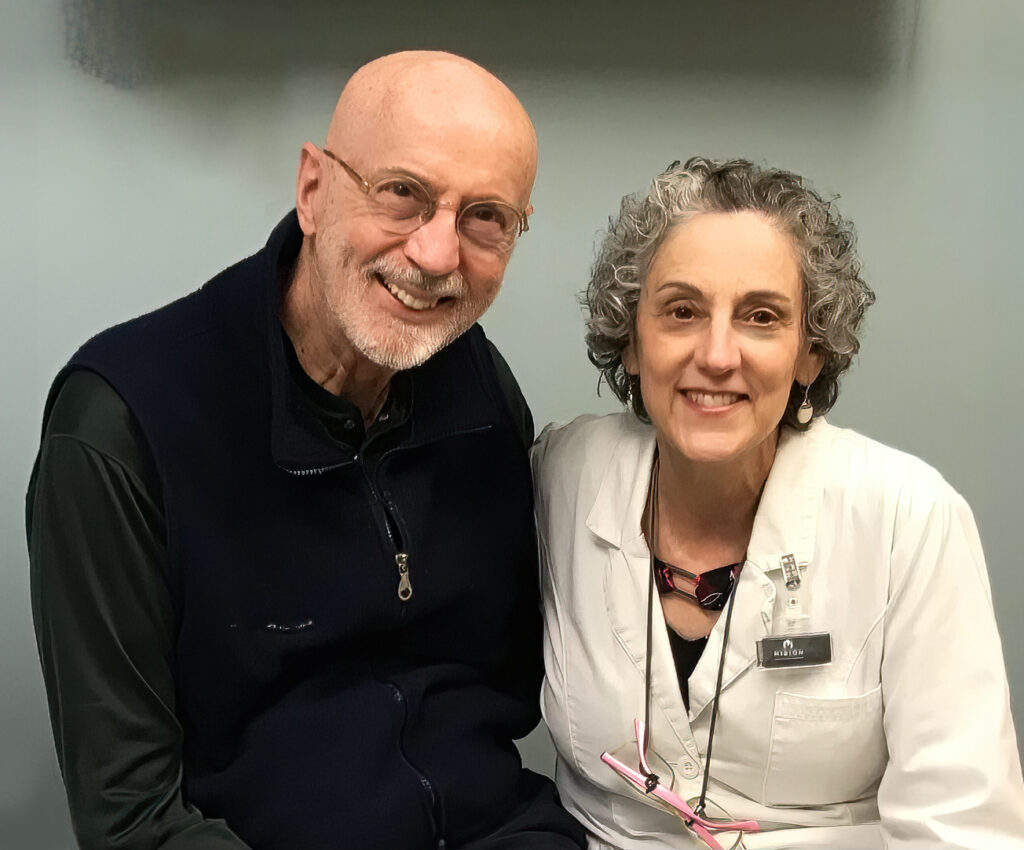

Over the last year, I’ve been introduced to many physicians, some stern, others pompous. Dr. Sue did not fit that mold. With her shades of curly gray hair, she seemed less like a medical doctor and more like a grownup version of the heroine from the musical Annie—spunky and optimistic with a dash of devilment. I was immediately drawn to her.

After listening to my heart and lungs and tapping both knees with a triangular mallet, she showed me a slide from the MRI scan. There it was: a small dot like a distant star in the constellation of my brain. Circling the lesion was a ring of fluid, perhaps the brain’s way of saying, “This does not belong here. Get it out.”

“Is it cancer?” I asked.

“Yes,” Dr. Sue said.

“And did it travel from my bladder?”

The doctor nodded. “Yes. The cell structure indicates that.”

What followed was a detailed explanation of how to irradiate the cancer. Dr. Sue said chemotherapy does little to destroy lesions in the brain. The recommended treatment was photon radiation. The first step was to map my brain for treatment with CT scans.

“Your head will be tattooed to perfectly align the beams,” Dr. Sue said.

“Wow,” I said, “my first tattoo. Can you do Tinker Bell with gossamer wings, thigh-high socks, and ballerina slippers?”

Dr. Sue stared at me with narrowed eyes. “I’m afraid not, pumpkin,” she said, her tone bubbling with playfulness. “We only do dots and dashes.”

“Geez,” I said, “you’d think a radiation oncologist with ten years of college, medical school, and residency would have more imagination than that.”

“Not so strange,” the oncologist said with a crooked smile. “We limit our imagination to dreaming of toys we’re going to buy with all our loot.”

She had me. I had no comeback.

***

The next day, I found myself at the Department of CT Imaging at Kadlec Hospital. I was introduced to a physicist who was responsible for making certain the equipment was properly calibrated and the radiation was accurately pinpointed.

What happened next was called the simulation session.

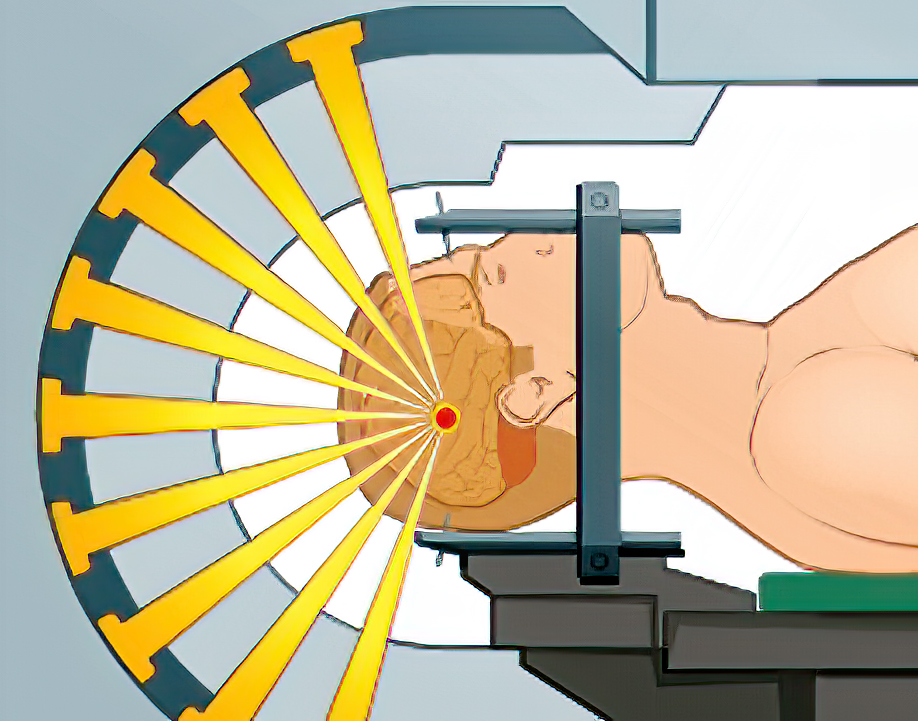

“The radiation beams will be delivered from four or five angles,” the physicist said. “In that way, the greatest damage will be to the DNA of the tumor with little damage to normal cells. Once the cancerous DNA is destroyed, it can no longer multiply.”

“I get it,” I said, which was a lie. I understood keywords—damage, DNA, destroyed—but the overall picture was still murky. “How does beaming from several angles diminish the chances of brain damage?”

“Multiple beams are designed to match the specific shape and size of the tumor.”

I crinkled my nose—an expression of bafflement.

“Think of it this way,” he continued. “Firing several beams for thirty to forty-five seconds each is less ruinous than irradiating a single beam for minutes.”

I tapped my fingertips. I understood.

I lay on a table, my head in a trough. A team of three heated a net of Kevlar plastic (the same material used to make bullet-proof vests), which made the fabric pliable. They then set the hot plastic around the back of my head. All three nudged the netting around the curve of my skull. A second piece was shaped around the contours of my face and chin. A cool towel helped to set the plastic mask in place. The end product is called, predictably, an immobilization device. In the end, I felt a bit like The Man in the Iron Mask by Alexandre Dumas.

(As it turned out, the “tattoos” were inscribed on the mask, not on my head. And so evaporated my chance to join the ranks of tattoo frenzy.)

After the masking, the simulation was followed by several brain scans, all of which were designed to create a three-dimensional map of my brain.

In the days that followed, the radiation oncologist, physicist, and dosimetrist would collaborate by analyzing the images for treatment planning including the mapping of the high-energy photon beams.

It was all very mysterious to me. I hoped my noggin would be capable of unraveling the mystery after the treatment.

***

On May 1, I was scheduled for the photon treatment, also called stereotactic radiosurgery. Although “surgery” is in the term, the procedure is not surgical. There were no incisions or drilling into my skull, thank goodness.

The physicist, a tall and broad-shouldered man with a healthy crop of gray hair, was clearly in charge.

I stared at an impressive mass of equipment called a linear accelerator.

“Does this work like an X-ray machine?” I asked.

“There are similarities,” the physicist said. “The difference is this machine releases photon energy that is 10,000 times more powerful than a typical X-ray.”

That made my eyebrows arch. “Ten thousand times,” I repeated, unable to check my voice from squeaking.

“Not to worry,” the physicist said. “Each beam is sculpted to conform exactly to the size and shape of the tumor. They are very precise pencil beams of photons in the form of gamma rays, which are a form of electromagnetic radiation.”

I held my head with both hands. “Uh,” I bumbled, “I was a literature major. What’s electromagnetic radiation?”

The physicist didn’t bother to chuckle. “Let’s see if I can explain in terms of a stream of photons.” He took a breath, which I interpreted as exasperation. “Photons are massless particles that travel in a wave-like pattern at the speed of light. Okay, so far?”

“Massless, wave-like patterns traveling at the speed of light,” I echoed.

“Right. Each photon contains a bundle of energy, and gamma-ray photons have the shortest wavelength and the highest energy in the electromagnetic radiation spectrum.”

At that instant, I was transported to another time and another place. I was in Montpellier, France, having dinner with French friends. We were chatting entirely in French. For the most part, I was following the conversation. But when I lost the thread, I discovered I could regain control by changing the subject. Invariably, it worked like a charm. If I controlled the topic, I controlled understanding. I was at that place with the physicist. “Uh-huh,” I said astutely. “And how many beams will be released?”

“Five,” the scientist said.

“How much damage is done to healthy cells?”

“Very little,” he said. “The good news is it can all be done in a single session. One and done.”

In less than two minutes, the team positioned me on the table—my knees folded over a triangular wedge, my head packed into the Kevlar shroud. When the face piece was screwed into the back of the mask, the fit was snug, almost vice-like. There was no chance of budging.

The mask covered my mouth, so I was left with breathing through my nose. For a while, I struggled with the idea of suffocation. You can do this, I said to myself. Take deep breaths and let the air slowly ease out. It worked; I was in control.

For the next thirty minutes, I listened to the hum of all five gamma beams and totaled their duration. One and two and three and . . . .” By my count, each irradiation lasted between thirty to forty-five seconds.

When the procedure was complete, a technician helped me to my feet. Although dizzy, I felt no pain.

“Thank you,” I said, grateful I could search, select, and articulate the words.

***

After the procedure, my neighbor and friend Alan Joseph joined me in Dr. Sue’s office for a debriefing session.

I’ve mentioned Alan in earlier chapters. He’s been with me throughout my year-long battle with cancer. But I’d like to take a moment to celebrate his character.

Alan is not an ordinary fellow. First, he’s graced with natural intelligence, further enhanced by a deep Ivy League education. His vocabulary is nearly as profound as his discernment. But that’s not the quality that impresses me the most. That would be his character. Alan is blessed with abundant compassion. In his lifetime, he volunteered to fight for lives on the brink of death after the 1989 earthquake in San Francisco followed by the 2005 Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. He’s dedicated to helping people in danger—including me.

Founded on his experience as a former hospital administrator, he’s been a faithful guide in my quest to defy death as long as possible. His council has been measured, his encouragement constant, and his friendship unequivocal.

And, once again, he was at my side when debriefing with Dr. Sue.

“I feel a little dizzy,” I said.

“That’s unusual,” the doctor said. “If you don’t feel better in two days, let me know.”

As it unfolded, I felt better in two hours, which was a relief. My mind was needlessly entertaining the nightmare of living the rest of my life in a fog.

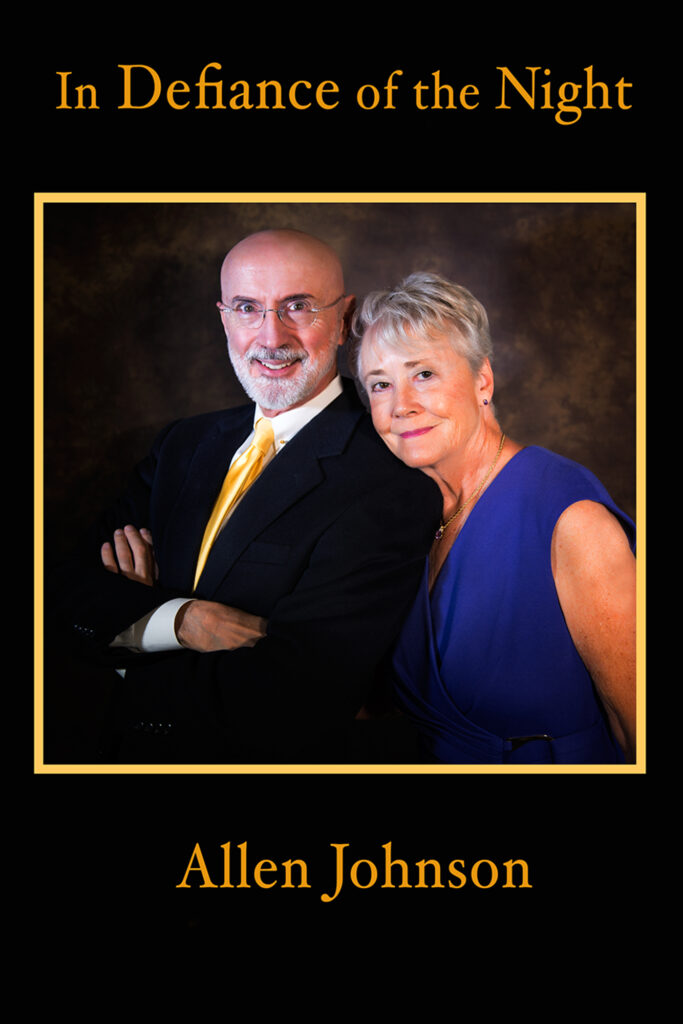

The conversation that followed was more chummy than medical. I asked if I could take Sue’s picture.

“With my mask on?” the doctor asked with a chuckle.

“Absolutely not,” I said.

“If we’re going to do this, let’s do it right,” she said. “Let’s get a portrait of both of us.”

Alan happily obliged by snapping the image.

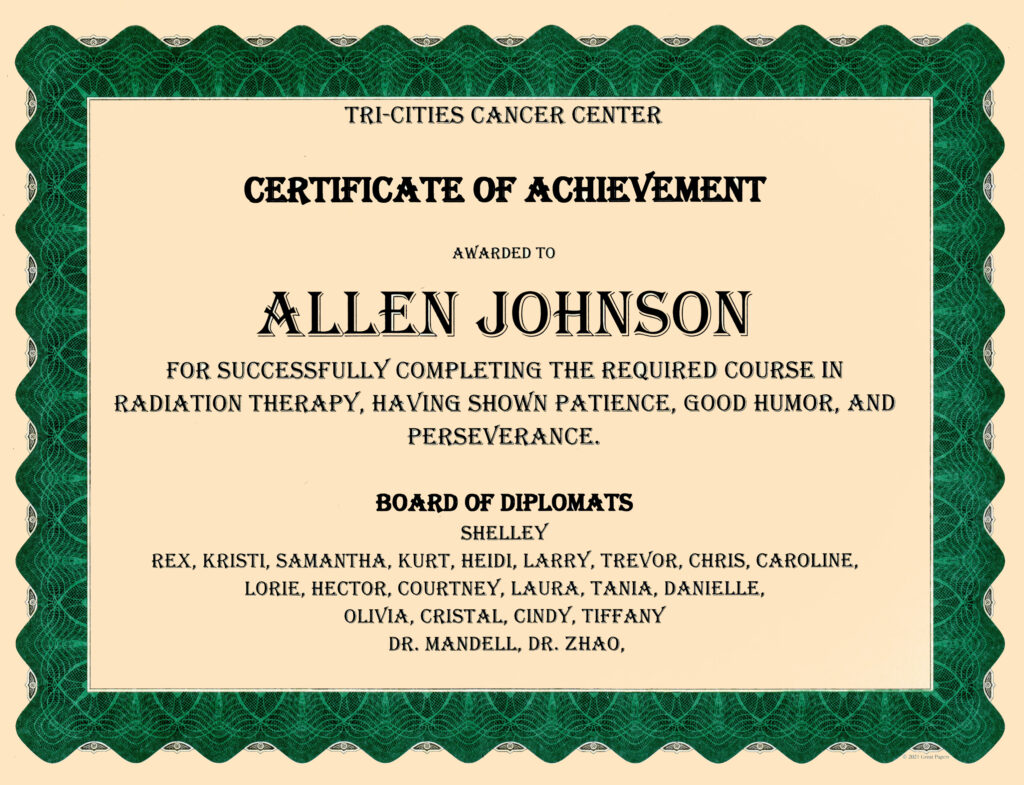

We were saying our goodbyes when a nurse knocked a single rap and entered the room. She approached and handed me an official-looking certificate of achievement, which read “To Allen Johnson for successfully completing the required course in radiation therapy, having shown patience, good humor, and perseverance.”

I’ve been treated with kindness throughout the year as filed in this autobiography. But in all that time, I’ve never been awarded a certificate of achievement. Repeatedly, the Kadlec Cancer Center proves to me they are dedicated to addressing our medical needs, yes, but equally intent on nourishing our souls. Thank you, Kadlec. You’re a class act.